In the mid-1930s, C. S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, on a walk, agreed that there was a dearth of good writing in “speculative fiction.” Science fiction did not become a popular term until the 1950s, but that is the sort of literature they were thinking about. “There is too little of what we really like in stories,” Lewis said. “I’m afraid we shall have to try and write some ourselves.”[i]

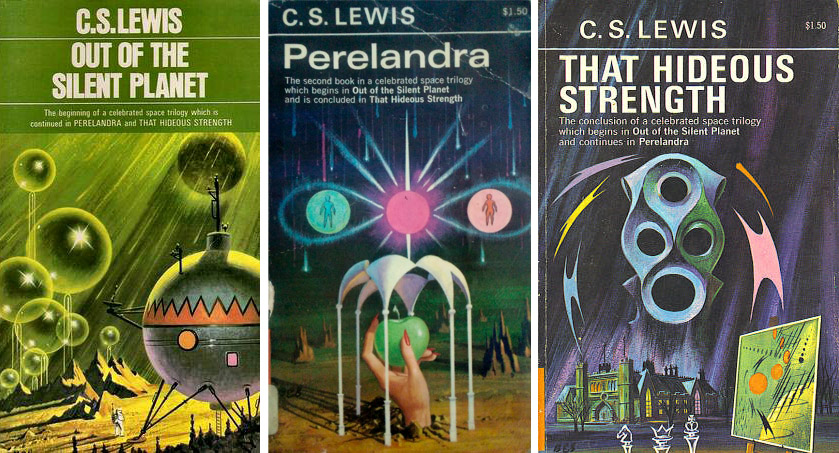

As the anecdote goes, they flipped a coin to decide who would write about time travel and who would take up space travel. Tolkien ended up with time travel and wrote two unfinished works related to Silmarillion stories (The Lost Road and The Notion Club Papers). That left Lewis with space travel, and he soon launched his famed The Space Trilogy.

Eighty years later, the relevance for our current times of his third novel is notable. That Hideous Strength takes place on Earth, or Thulcandra, “the Silent Planet,” following the first two novels on Malacandra (Mars) and Perelandra (Venus). . Having returned from his adventures in Deep Heaven, the philologist-turned-hero, Elwin Ransom, brings together a company of people to thwart the dystopian aims of a British technocratic network.

Can a technocracy really happen? Can technicians and scientists truly rule society? Lewis actually had a deep concern about this prospect. Most readers of Lewis are aware of his theological writings and his fiction. But he also wrote over thirty books and articles that specifically addressed his concern for the way applied science, undergirded by a mechanistic worldview, would pose a serious threat to the modern world. Chief among his worries were innovations in genetic engineering.

One of these writings is The Abolition of Man, which includes a statement that is found verbatim in That Hideous Strength (THS). “What we call Man’s power over Nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument.” Lewis stated in his preface that THS was “a ‘tall story’ about devilry, though it has behind it a serious ‘point’ which I have made in my Abolition of Man.” Transhumanism had not been coined as a term in Lewis’ time, but similar issues involving evolutionary progress and genetic experimentation were part of what he observed in his university milieu.

After the publication of THS in 1945, critics claimed Lewis was being anti-science, a charge often leveled in our own day against anyone raising questions about the promotion of new technologies. Lewis routinely denied this charge, explaining how he did not oppose science but rather “Scientism,” the unchecked belief in Progress which allows for no “wholesome doubt,” as he phrased it in his essay, “A Reply to Professor Haldane,” in Of Other Worlds.

In both Abolition and THS, Lewis illuminated connections between an emerging relativistic philosophy in academic settings that disregarded the role of moral values inherent to all human cultures and the rise of Scientism (justifying social control in the name of ideological progress). Abolition is a treatise on how society could ‘progress’ according to a new set of values, dehumanizing as they are, which enabled technocratic control with no constraints. THS is simply a fictional account of seeding this trajectory in western society.

What kind of book is THS? Even in relation to the first two books of The Space Trilogy, THS is quite the oddball. Lewis called it a “modern fairy tale for grown-ups.” Should it be grouped with dystopian novels? Is it a satire on technocracy? A socio-spiritual thriller? Since Merlin is resurrected in the book is it Arthurian fantasy? Or perhaps, in keeping with the title, a Tower of Babel myth? “The shadow of that hyddeous strength / sax myles it is in length” stems from David Lyndsay’s 1555 poem, The Monarche, which is about Babel.

One important aspect distinguishing the trilogy from general sci-fi is its moral-spiritual dimension. Lewis saw how early forms of science fiction had promoted a materialistic worldview. Why not use sci-fi, he thought, to subvert this worldview and present an alternative, Christian-friendly mythology? In this light, THS offers a prophetic “radical challenge to the accepted wisdom of his own generation,” exposing these established truths as “shadows and smoke.”[ii]

I would like to offer three reasons why this book should be read or reread in our contemporary situation. Here now is an appetizer:

1. Science fiction reflects real aspects of the present, going into the future.

2. The collusion of science and state powers forms a dangerous mix.

3. The educated tend to be persuaded first by propagandistic media.

But first, a bit more about the plot line. Having encountered innocent creatures and spiritual beings in other planetary worlds, Ransom returns to the Silent Planet as a transformed person with heightened spiritual capacities, honed to discern malevolent powers. These fallen Macrobes now seek to dominate the world through a socio-scientific planning agency called the National Institute of Coordinated Experiments, also known as N.I.C.E. Two new protagonists, a husband and wife called Mark and Jane, must not only find their way in the midst of this epic struggle; they must also find themselves and each other in the context of their failing marriage.

The stark contrast between Mark and Jane is noteworthy. He wants to be drawn into the inner ring of N.I.C.E., while Jane, with her dark, clairvoyant dreams, does not want to be drawn into Ransom’s fellowship. Ransom’s headship contrasts sharply to the head of N.I.C.E. Indeed, it is a literal head, severed and kept alive with breathing tubes! This Head is not only an oracle for fallen spirits; it is a prototype of Man Immortal, freed from organic co-dependencies. Ultimately, the technocratic venture “pulls down Deep Heaven” (namely the planetary spirits) upon itself, and the climax of the story mirrors the confusion motif of the biblical Babel narrative.

Is it necessary to read Out of the Silent Planet and Perelandra before THS? It certainly helps, but I would lean more toward saying it is not necessary. I have created a readers’ guide which serves to help new THS readers. Lewis also peppered his novel with literary references and obscure historical figures. The best annotated guide to quotes and allusions is the webpage made by Arend Smilde. Now, to the three reasons for reading THS. All three are in concert with Lewis’s own motivation for writing The Space Trilogy.

First, science fiction reflects real aspects of the present into the future. Perhaps this goes without saying. Sci-fi authors are generally observant of social realities around them, and they exaggerate them for the future. When Huxley wrote his nonfiction book, Brave New World Revisited (1958), he explained that when he first wrote his dystopian novel (1932), he figured it would take a couple centuries before his speculative visions would take root. He was astonished to see so many of his projected realities incubating already in the 1950s.

Young adults can often sense the beginnings of greater social control. In the first couple of months of the Covid pandemic when universities were the first to lockdown, there was an interesting trend. College-aged students, through word-of-mouth promotion, were reading the classic novels 1984 and Brave New World. This uptick in dystopian book sales marked an intuitive impulse among younger adults for tracking subtle social shifts.

I think Lewis shared this sort of tacit knowledge for what was shifting in his day. Sanford Schwartz points out that Lewis—fully aware of how Nazism and communism threatened to transform humanity with subhuman agendas—recognized subtle drifts within his own democratic, postwar England. He writes:

The capacity for the biotechnical transformation of humanity – driven by the extraordinary developments in genetic, robotic, information, and nanotechnologies – increases on an almost daily basis, and even if (for now) we in the West are somewhat less haunted by the specter of state-enforced eugenics, it seems as though the major concerns of The Space Trilogy are becoming ever more ominous as we move further into the twenty-first century.[iii]

Reading THS can help us understand how young adults have detection instincts, similar to the way they can smell out hypocrisy in churches. THS, thus, can serve as a great springboard of conversation. Reading sci-fi, especially when it carries a moral and spiritual message, is a way to sharpen our capacities to see present trends. It helps us to become better “seers.” We come to detect the subtle trends by first seeing them in larger fictionalized settings.

Second, the collusion of science and state powers forms a dangerous mix. The beginning of THS is an interesting study of how the joining of powers is essential to an agenda of social control. “The N.I.C.E. was the first-fruit of that constructive fusion between the state and the laboratory,” wrote Lewis. This nexus of university and government stakeholders soon added its own technicians, engineers, legal staff, and secret police. And, of course, a media division. Mark, a statistical sociologist, was asked to write articles to influence public opinion.

In his farewell speech of 1961, President Eisenhower warned Americans about the dangers of combined powers. The well-known “military-industrial complex” meme comes from this speech. By “complex,” he meant the unwarranted combination of powers which are best kept separate. Lesser-known is a second complex he considered equally dangerous to our liberties: a techno-science and government complex.

On one hand, Eisenhower feared that too much scientific research was being driven by government funding and oversight. On the other hand, “we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.” This double threat can more easily be seen through the lens of the First Amendment with respect to Church and State powers.

In the Cold War context there was a strong drive to build up our military hardware (and sell it worldwide) in relation to a perceived threat. In our pandemic times, we can see a similar dynamic with the way government agencies have immense power to both define the public health problem and present the pharmaceutical solution. “There is a recurring temptation to feel that some spectacular and costly action could become the miraculous solution to all current difficulties,” stated Eisenhower.

In this same era, Lewis wrote his essay, “Is Progress Possible? Willing Slaves of a Welfare State.” He noted how a “new oligarchy” would call the shots over politicians, aiming to control all food and medical care systems worldwide. “Nothing but science, and science globally applied, and therefore unprecedented Government controls, can produce full bellies and medical care for the whole human race: nothing, in short, but a world Welfare State.”[iv] Traditional wisdom for food production and health care would seemingly never do.

Lewis was not alone in his concern over the colonization of human minds and bodies. G. K. Chesterton, in his 1922 book Eugenics and Other Evils, wrote about scientific officialism. “The thing that really is trying to tyrannize through government is Science.”[v] He was mostly concerned about the Scientism of his day that envisioned a new and better humanity. Lewis likely knew Chesterton’s opening line: “The wisest thing in the world is to cry out before you are hurt. It is often essential to resist tyranny before it exists.”[vi]

Reading THS can help us sharpen our awareness of how power complexes form to advance multisystems of control. We may think sci-fi levels of social control can only happen in a distant future. Currently, we prefer to focus on the positives of new technologies and less on the risks. However, when the benefits are repeated and posed over and against the ‘malefits’ (a term coined by Tolkien), it is hard to trace the aims of colluded power upon public opinion. This leads us to a final reason for reading THS.

Third, the educated tend to be persuaded first by propagandistic media. Lewis had a keen sense of how news media could sway the masses, especially the intellectual top layer. The chief of N.I.C.E.’s secret police (who just happens to have a penchant for torture) explains to Mark how technocratic control requires people to be in a constant state of polarization. “Isn’t it absolutely essential to keep a fierce Left and fierce Right, both on their toes and each terrified of the other? That’s how we get things done.” Stirring both sides to demonize each other is an effective way to keep people’s attention off higher networks. In the end, those networks are viewed as being benign and neutral.

“Of course we’re non-political,” says Chief Hardcastle. “The real power always is.” This oligarchic insight was well understood by Jacques Ellul, who wrote about technocratic totalitarianism. In The Technological Society (1954), he frequently explains how political power is always overshadowed by technological power. He is not talking about the power of technologies, but the value-driven power of technique, a hideous force that dominates all aspects of modern life.

As the conversation continues, Mark expresses his doubts that this sort of propagandistic tactic can effectively sway educated people. Hardcastle upbraids him. “Haven’t you realized it’s the other way round?. It’s the educated people who can be gulled. All our difficulty comes with the others.” She goes on to explain how the educated class is conditioned to absorb news religiously on a daily basis, rewarding themselves for being “in the know.”

Walter Lippmann, in the Wilson era of WW1, was a proponent of propaganda to influence public behaviors. He distinguished “the specialized class” from “the bewildered herd.” The educated elite of the first group, being society’s thinkers and planners, should be the first target for information designed to bring mass approval to a new agenda. Raising anxiety around a growing enemy and posing a solution for the good of society had to effectively work among highly schooled people before it could spread through the herd.

Later in THS we learn how censorship, selection, and the seeding of half-truths became mainstays of newspapers overseen by N.I.C.E. Garnering gradual approval for future changes was a vital task of the press. “Citizens” allegedly predicted there would be rising troubles to come and an unnamed person said, “We need more police.” Eventually a small article stated that local police were incapable of dealing with the new population. This is not spin; this is crafting news for desired compliancy.

Lewis was a keen observer of the press, citing British examples in THS of how journalism appealed to the intelligentsia of his times. He also placed “Ransom and Company” in a separate category. This group truly held spiritual insight into the events of the day, able to read subtexts that had larger implications. THS can help people of faith stretch new muscles in the realm of reading the signs of the times. It reorients the way we analyze information which obscures hidden truths.

In closing, there are certainly additional reasons for reading That Hideous Strength. One of my favorite threads throughout the story is the reluctance within both Mark and Jane to undergo their respective conversion experiences. The beauty and joy that spills from the visitation of the planetary gods is an amazing scene for any reader to enter vicariously. And Merlin rises from the dead to help win the day!

For Inkling fans, it is worth spying out the subtle influences of Charles Williams and Owen Barfield on Lewis’s thinking. Between the Arthurian Logres legacy and a direct mention of Barfield’s “ancient unities,” the book is filled with Inkling-inspired elements. In the preface, Lewis even makes mention of “Numinor” and “the True West,” prior to Tolkien’s publications.

For myself, this book is a timely read in relation to themes of social control. If Lewis in the 1940s felt compelled to expose nascent expressions of technocracy which he intuited among his scholarly peers, I feel all the more compelled, eighty years later, to track ever greater complexes between political, scientific, corporate, and media powers. At minimum, reading THS can help us embrace what Lewis prized as “wholesome doubt.”

Ted Lewis is a restorative justice practitioner and trainer, founder of the Restorative Church project, and also serves as the executive director for the International Jacques Ellul Society.

[i] Tolkien, Letters, no. 215: 298.

[ii] Alister McGrath, C. S. Lewis—A Life (Carol Stream: Tyndale House Publishers, 2016), 235.

[iii] Sanford Schwartz, C. S. Lewis and the Final Frontier (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2009), 7.

[iv] C. S. Lewis, “Is Progress Possible? Willing Slaves of the Welfare State,” in God in the Dock (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2014), 352.

[v] G.K. Chesterton, Eugenics and Other Evils (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1927), 76.

[vi] Chesterton, 3.