Radix board member Ryan Pemberton recently interviewed Dr. Jason Lepojärvi on the topic of Women and the Inklings. Ryan Pemberton is a former scholar-in-residence at the Kilns, C.S. Lewis’s former home in Oxford, former President of the Oxford University C.S. Lewis Society, and author of two books: Called: My Journey to C.S. Lewis’s House and Back Again (Leafwood Publishers, 2015) and Walking With C.S. Lewis (Lexham Press, 2017). Also a former President of the Oxford University C. S. Lewis Society, Dr. Jason Lepojarvi is a tutor on the work of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and the Inklings, and a frequent lecturer on topics involving C.S. Lewis theology of love, his dissertation topic, which he completed at the University of Helsinki in 2015. His research has been published broadly in journals, including Harvard Theological Review, The Journal of Inklings Studies, and Religious Studies.

Radix: Well, thank you, Dr. Jason Lepojärvi, for joining me in this conversation pertaining to the role that women played in the lives, thought, and theology of the Inklings, and specifically that of C.S. Lewis. To start off, could you give us a little background on yourself and your work in this area?

JL: So I am actually half Canadian and half Finnish. I have lived in a few different countries, including England, where I spent four years at Oxford. I was wrapping up my dissertation on C.S. Lewis’s theology of love at the time, which I defended in Helsinki, not Oxford, but I was working in Oxford.

My interest in Lewis actually started early on, when I was about 19 or 20 in the Finnish military. That was the first time I ever picked up a book by Lewis. So I was not brought up a “Narnian.” I started with The Problem of Pain and I just kept reading from there. And I just fell in love with his style and content, because he marbles the two together quite well.

Radix: Yes, he does.

JL: Then I did a master’s in theology where I worked on Pope John Paul II’s theology of the body. When it came time to do my dissertation, I wanted to pair John Paul II with C.S. Lewis because I thought they had a lot of interesting things to say together. But the more I read Lewis, from a scholarly point of view, the more I realized I could only do one or the other. So I continued with Lewis.

I am also a former president of the C.S. Lewis Society at Oxford, as were you, Ryan. And right now I am a former assistant professor and Chair of Religious Studies at Thorneloe University at Laurentian. But the university was completely axed and shut down [in the spring of 2021]. All of the faculty had to be laid off due to financial woes. So, since this summer, I’m merely a fellow of that university. And I am looking for my next adventure.

Radix: But you are still continuing your work in the area of Lewis and the Inklings, in terms of writing and tutoring?

JL: Yes, absolutely. I teach one-on-one Oxford-style tutorials online through my website, studycslewis.com, and I participate in various conferences on the Inklings; one was held at Taylor University; another on Lewis and friendship with women at the American Academy of Religion this fall; and then another will be next winter, at Hillsdale College.

Radix: Thank you for some of that background on your work with Lewis, along with these different phases of your journey. So for our readers, can you give us a little background and biographical information on Lewis’s own life?

JL: It’s hard to imagine anyone who hasn’t already read something about or by C.S. Lewis. I imagine that many readers out there will know about him. One of the reasons that he is popular even today, nearly 60 years after his death, is not only because of his 40-plus books and thousands of letters, but because he was such a versatile and timely writer. People find that what he had to say is topical and refreshing. His books and letters speak to a multigenerational audience.

By profession he was a professor of English literature, first at Oxford for a quarter of a century, and then for his remaining years at Cambridge. So that was his bread and butter, as it were. In his free-time he wrote more popular books for a broadly Christian audience. And it’s those books that people first come across – Mere Christianity or The Screwtape Letters, to name a few. But then people might come across other works, like I did – the more academic books, like The Problem of Pain. And even his more scholarly works and essays are very recommendable. In addition, there is his poetry, or even books that don’t explicitly speak about Christianity at all, like Till We Have Faces, which is one of my favorites among his novels.

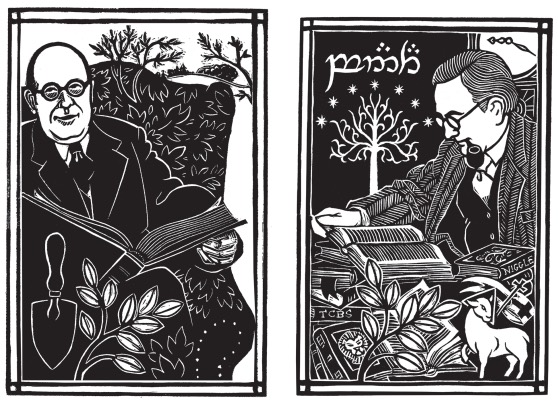

Lewis is also known because of his close association with the Inklings, which was a circle of Oxford-based intellectuals and authors. I think Alister McGrath, an Oxford professor and Inkling scholar, has called the Inklings “a constellation of stars rotating around its two suns, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien.”

Radix: That is an eloquent way of describing what the Inklings were, and a fantastic image as well. I am going to hold onto that. Thank you.

JL: That might be partly inspired by Michael Ward’s Planet Narnia book. Anyway, the Inklings would meet twice a week, once at a pub and once in Lewis’s room at his college to discuss Christianity, faith, and their interest in literature. Hence the word, “Inkling.” And it just happened that all of them were men. I think this was by design. And this speaks to our topic.

Radix: Yes, it does. Before we get into women and their influence on the Inklings, can you speak a little bit more about who else, other than these two “suns,” made up this constellation, as it were?

JL: If you had to choose the primus motor of the group, it would probably be Lewis. Tolkien was very influential as well, and he would sometimes invite friends to join the group too. But it was Lewis, more often than not, who would bring visitors in. He had a very “catholic” taste in friendships and could appreciate different kinds of people.

The two other quite famous members of the group were Owen Barfield and Charles Williams. Both were very prolific writers. Barfield wrote on the development of language and consciousness: Saving the Appearances and Poetic Diction are among his most notable works. Charles Williams was a writer of theological thrillers and an editor for Oxford University Press. That’s how he got to know the group. He worked in London, but during the Second World War Oxford University closed shop in London and relocated to Oxford. And that’s when he got to know the Inklings better and became a member for a number of years before returning to London. There were many others as well, even as many as a dozen, depending on what the criteria for membership were. These included people like Dr. Robert Havard, Lewis’s medical doctor, and Lewis’s brother, Warnie, who was one of the first, the last, and the most faithful.

Radix: So, as you have already said, these are all men. And yet there is reason to have some conversation about the impact of women on this group – their thought, their work, and their literature. So maybe we can talk about them. Maybe we could start with Mrs. Moore? Who was she, and what was her relationship to Lewis?

JL: Yes. It’s good to start with her and women who knew the members of the Inklings before they became prominent authors. So we could even start with their mothers. For Lewis or Tolkien, just as an example, their upbringing is important. And their mothers were often their first educators, and in positions of authority to teach and impart wisdom. But Mrs. Moore became a kind of surrogate mother for Lewis [Lewis lost his own mother to cancer before the age of 10]. The story goes that during the First World War, Lewis and a friend, Paddy Moore, made a pact to take care of the other’s parent if one died. When Paddy did die, Lewis moved in with Mrs. Moore and Maureen Moore, Paddy’s sister. They lived together for decades, almost right up until Mrs. Moore’s death after she had moved to a retirement home.

Radix: This was in the late [19]40s or early [19]50s?

JL: Yes, exactly.

Radix: So really, during the time of Lewis’s involvement with the Inklings, he was sharing a residence with Mrs. Moore?

JL: Yes, and that is important to remember because it guards us against a kind of misleading and simplistic view of Lewis living as a bachelor. He was a bachelor but he lived with women, of multiple generations, for most of his life.

Radix: Just to go one step further in terms of that influence, can you describe Mrs. Moore a bit – what sort of influence she might have been, what type of ethos she would have brought to his domestic life?

JL: She was not a Christian and she was not a scholar. So her influence on Lewis was not one of faith or letters. And that would have precluded a friendship from having evolved around the two, according to Lewis, since his understanding of friendship was closely connected with shared passions and interests. There is also good reason to believe that for some time there was a romantic relationship between them. Very soon this changed, to become a mother and son kind of relationship for the rest of their lives. The relationship would have been a marbling of affection and agape, not so much philia, friendship.

Radix: Because of that lack of shared passions?

JL: Exactly. And the same might be said of Tolkien’s relationship with his wife, Edith. So while they had a very loving, very faithful, very fruitful relationship, it wasn’t necessarily a friendship in that sense of the word.

Radix: According to Lewis’s definition?

JL: I think Tolkien would have shared a similar view. But they did have friendships with many women, just not all women, and not even all the important women in their lives. We’ve got to remember that this is not a belittling thing to say, that they weren’t friends. They have a specific understanding of friendship. I think, for many of us, we might say, oh, obviously they were friends; you know, you can be friends with anyone if you spend a lot of time with that person. But I think they would quibble with that definition of friendship. For them a friendship was different than an acquaintance.

Radix: I’d like to bring up a few more names, and there are maybe some that you would like to add. Can you tell us a little bit about Ruth Pitter, and that relationship?

JL: Sure. I just want to address one thing before we go on. Alister McGrath, in his biography, mentioned that the only defect in the Inklings group was that there were no women. Now, I personally dispute that. That is like saying that a group of only women is inferior. It’s not true. Instead, this is the sort of thing that we are supposed to say nowadays when we talk about diversity, you know, as in the case of an all-male panel, for example. But I don’t buy into that. If there are a group of four or five women, that’s a beautiful thing in itself and it’s not marred by the absence of men. So in the same way, I would push back at Alister’s comment. Had women been a part of the weekly meetings, it would have been a different thing. Sure, a wonderful and beautiful thing in itself, but it wouldn’t be the Inklings. Not as we know it. And it doesn’t mean that Williams or Barfield or Lewis objected to mixed groups. Quite the contrary. They were part of other literary groups throughout their lives that were mixed. The Cave is an example of such a group. Both Lewis and Tolkien belonged to that group, along with other Oxford female scholars.

Radix: I appreciate you naming the fact that this was one of the many groups that they were involved with. So as you point out, it wasn’t the case that there weren’t any female influences.

JL: Exactly. It wasn’t insular at all. And so you mentioned Ruth Pitter. She is very interesting. She was an English poet with whom Lewis had a real friendship. And I mean friendship in Lewis’s sense, that they shared common passions and interests.

Radix: That they were looking in the same direction, and were excited about some of the same things.

JL: Yes. Not that they were necessarily seeing eye to eye, but looking in the same general direction; looking in the same direction from shoulder to shoulder: that would be Lewis’s preferred image. So yeah, to read the letters between Lewis and Pitter is interesting. The letters are quite personal. And Lewis had that kind of relationship with other women, as well. Though not in just the pen pal kind of way. Obviously, the main method of communication was letters. And while he had lots of fan letters, this relationship between he and Pitter was more reciprocal. Lewis gave a lot of himself in these letters and asked genuine questions. But it was also flirtatious, which was rare for Lewis, who was never flirtatious. Joy Davidman’s biographer, Abigail Santamaria, says that she went through all of Lewis’s letters to women – and they were in the thousands – and they were never inappropriate. But mild flirtations surfaced in some of the letters to Ruth. I was actually talking to Owen Barfield’s grandson, and he mentioned that Charles Williams’ wife was very close friends with Ruth and that they had a pact in trying to pair Ruth with Lewis. Don King, an American Inkling scholar who edited Joy’s poetry, suggested in one article that the only reason that Lewis ended up marrying Joy instead of Ruth was because Joy tried harder. She was, in fact, very persistent. Ruth was waiting for Lewis to make the move.

Ruth and Lewis did see each other in person. He would go visit her and she would visit him, though not that often. The main form of communication was in exchanging letters. This applied to Lewis and Dorothy Sayers too. Though Lewis and Sayers never shared anything romantic.

Radix: Let’s transition to Sayers. Can you tell us a bit about her and about their relationship?

JL: For Lewis and Sayers, it was mostly philosophy and scholarship and plays that they shared interests in. If Dorothy had been a “Dick,” short for Richard, she would have been an Inkling for sure. She was a prolific author, a versatile scholar, playwright, poet, public commentator, and apologist. And I think she developed a close relationship with Lewis, but above all, with Charles Williams. In fact, when Lewis conceived the idea of honoring Williams with an anthology of collected articles Sayers was the only non-Inkling member, and happened to be a woman. Lewis invited her to contribute, which she did.

Gina Dalfonzo, the author of the recent book Dorothy and Jack, which is a very good book, shows the evolution of their friendship. Gary Tandy from George Fox University and Laura Simmons have also done work on the Lewis-Sayers relationship. Anyway, that relationship starts off with Sayers writing to Lewis. She was much better known at the time, so Lewis was very flattered. Actually, another time something similar happened was when Evelynn Underhill, a leading authority on mysticism, similarly sent Lewis a fan letter, and he was really touched. But with Sayers, Lewis developed a friendship that included a good deal of vulnerability, especially concerning his loss of Joy. The letters are very candid, raw, and vulnerable, and it’s interesting that Lewis would choose Dorothy to be so forthcoming to.

To change direction a bit, your readers might find it interesting that the early Lewis can be justly described as quite a sexist figure. His early pre-conversion diary, All My Road Before Me, is quite open about that. There’s a lot of ugly, unflattering language about individual women and the female sex in general. For example, he says, “apart from few exceptions, I loathe the female sex.” That’s pretty awful!

Radix: Not really mincing words there.

JL: Not at all. Though in that diary, he is very cynical about men as well. Interestingly, when it comes to literary female authors past and present, that same diary, spanned across a number of years, has only positive things to say of women. Like for the illustrator Fiona McDonald, and he just praises authors like Jane Austen. Speaking of this, and I can’t prove it, so am indulging in a bit of pop psychology, but I wonder if in his real life some of the women he knew early on, and I am talking about the female guests who would live with Lewis and Mrs. Moore, influenced him in an unfortunately negative way. We know that many of the women who stayed in Mrs. Moore’s home during WW II were not educated, some of them were dishonest, some abused, and some lied and could betray trusts. And I wonder if this had an undue impact on his earlier views of women. I say this because there is such a discrepancy between the praise he gave to some women as compared to others that were in his life at the time. Anyway, that is just my hypothesis.

When Lewis becomes a tutor, interestingly, the first students he taught were women; a group of seven, a septet from Lady Margaret Hall. He’s very critical of the work of some of them, but praises the work of others in the group. Anyway, I am curious about all this.

Radix: That all is very interesting.

JL: Speaking of both Lewis and Tolkien, both supported female higher education in their own way. But Tolkien far out shadowed Lewis. John D. Rateliff’s scholarship has demonstrated this nicely, that Tolkien put in a real effort to seek out and elevate women in the academy. So much so that the J.R.R. Tolkien Professorship of English Literature rotates among formerly female colleges. And this is not a coincidence.

Radix: Interesting.

JL: Yes. And this is a correction that is new. Humphry Carpenter, one of the early biographers, who was very perceptive in a number of ways, set a few false tracks that have only recently been corrected. One of them was to portray the Inklings as an all-male society and almost sexist or even misogynistic, suggesting that they didn’t view relationships with women as possible. This is totally untrue. In fact, Lewis’s The Four Loves is one of the first books that not only admits and recognizes friendship between the sexes, but welcomes, very strongly, friendships between the sexes, which were segregated for so long. He says that, previously, when men and women couldn’t work side by side, philia couldn’t develop. However, now that things were changing, real friendships could develop.

Radix: So, Lewis is saying that this sort of twentieth-century phenomenon is the beginning of something.

JL: Yeah, and I think it’s quite a persuasive theory. You know, I too had my earlier prejudices; not against Lewis, but more against Tolkien. To use a virtue metaphor, I thought that Lewis was the golden mean, and that a person can either fail by defect or excess. My theory was that Lewis walked the talk, that he developed friendships with women. And that Tolkien was the defect. That he kept a kind of “Billy Graham Rule” and kept his distance. And then that Williams was the excess who transgressed appropriate healthy friendships with women, which he did. However, from the literary and biographical evidence, I think now that it was Tolkien who outshone Lewis.

Radix: So there was some course correction that was needed, even in your own mind – that the issue is much more complex?

JL: Yeah, absolutely. One of the things that helped create a negative image of Tolkien was Carpenter’s collection of letters. We have this letter from Tolkien to his son [Michael], who is wanting to marry a nurse who has taken care of him. In that letter, Tolkien, understandably alarmed at his son’s wanting to marry after only a few weeks of knowing this woman, comes off as very cynical and skeptical about the possibility of philia developing between the sexes. This despite the fact that his own life has proved the opposite to be true. So, it’s more likely that he has given his son advice tailored specifically for him, knowing the temperament and character of his son. And that explains the odd and peculiar emphasis of this letter – a letter that included the beautiful image of a marriage being like a companionship on a shipwreck, where both partners in a romantic relationship are fallen human beings. While this companionship can provide a great deal of joy, it isn’t to be overly idealized.

Radix: No one we meet is outside the postlapsarian condition in which we find ourselves – including the one who appears idyllic.

JL: Yes, including the one who makes you so happy. Because they are in the same condition as you. They are companions in this shipwreck. And we are all in this shit together.

Radix: That really is helpful language: “companions in shipwreck.”

JL: And I think this is the perspective that Tolkien took in the many relationships he had with women in his life. As far as the letter goes, I think many scholars took it as Tolkien trying to dissuade his son from marrying. And, you know, that marriage did end in divorce, so perhaps the letter was far-sighted? But I think the letter was a wake-up call to his son – a call to arms, as it were – that he was to take women seriously. They are companions in shipwreck. If you marry this woman, she is your soulmate. True love is the fruit and the reward of the work of love, not a precondition of relationship. He is saying to his son, if you marry this woman, you love her for the rest of your life. You do not discard her when the feelings dissipate.

Radix: Last but not least is Joy Davidman and her influence on Lewis. Can you speak more about that?

JL: Joy Davidman was an American poet and writer. She was formerly Jewish and communist, and she had two sons, David and Douglas. And largely due to reading Lewis’s writing, she and her husband converted to Christianity. Fast forward: she ends up marrying Lewis and lives with him in Oxford for a couple years before succumbing to cancer.

Joy’s relationship with Lewis is best described in Abigail Santamaria’s biography called Joy. Now, Abigail had a positive prejudice about Joy and the relationship that Joy had with Lewis. Abigail thought the relationship must have been a wonderful fairy tale, but it’s a lot grittier than that. Joy is a page-turner and Santamaria is a phenomenal writer. Anyway, what we see is that the relationship starts as philia, as friendship. It actually starts as a pen-pal relationship, and then slowly, very slowly, in fact, since it is one-sided, it develops into eros: Joy obviously has a more-than-friendly interest in Lewis. Lewis is the object of her desires. We know this from reading some of the candid poetry she wrote, even when she was still married to her former husband. But it’s not until they divorce and Joy moves with the boys permanently to England that something happens in Lewis as well, where he develops, or responds to, this romantic interest. But above all, it was a real friendship. Warnie had some beautiful things to say about Joy after she died. He praised her and said how grateful he was for the friendship he and Lewis had with her while she was at The Kilns, their home.

When it comes to what people think that Lewis thought about relationship, I’d say four out of five assume that Lewis didn’t believe in friendship between the sexes. Yet in The Four Loves, not only does he say it is possible, but that it is a virtue; that in male-female relationship, it can greatly contribute to increased eros; that nothing can so enhance the erotic element as realizing that your significant other can enter into the relationships with friends that you already have. Anyway, I think that people gloss over these beautiful sections that praise the relationship between female and male friendships.

Radix: So in terms of Joy being brilliant, this would have contributed to a great connection.

JL: Absolutely.

Radix: She was a child prodigy, right? I think she started at Columbia University at age fourteen, and also had a very high interest in literature. In fact, she was well accomplished in literature in her own right. So she really would have been able to hold her own with him.

JL: That would have certainly added to the friendship. Warnie says in his diary that “she loved debate and she loved beer and we all had a merry time together.”

Radix: [Laughter]

JL: That’s perfect, right? Debate and beer; where do I sign up? So yeah, she could certainly hold her own and could push back. That is something that the Shadowlands movie got right.

Radix: Could you speak about the direct influence of Joy on Lewis’s work?

JL: According to Lewis himself, Joy had a huge role to play in the book Till We Have Faces; which is one of my favorite books.

Radix: And Lewis’s as well.

JL: Yes, that’s right; it was. And some women who read that book say that the internal dialogue that Lewis uses for the female character is very persuasive, and authentic enough that it might as well have been written by a woman. Lewis, in fact, says that Joy served as a midwife, saying that “I am pregnant with book, and Joy served as midwife.” So he would write a chapter and run down to Joy and have her read it and give her critique of it. Yeah, some scholars see an influence in Lewis’s work from Joy, that she inspired him in a way.

Radix: Very interesting. So just to close, Jason, how would you sum up the influence of women on the Inklings?

JL: I would say that women influenced the members of the Inklings all their lives, from early childhood right up until their very deaths. In many ways, using the idea of The Four Loves for vocabulary, they had relationships of affection, of friendships and of eros with many women. And while none of those women were official members of the inner circle of the Inklings, those men had really meaningful relationships, including friendships with, women. That is how I would wrap it up.

Radix: A fitting conclusion. Thank you so much for taking the time to join me in this conversation.

JL: My pleasure, and I am still learning.

Radix: Here’s to more learning.