Note from the editor. As our readers will know, Radix believes in art. Art, when properly received, touches the heart and soul in profound ways. This unique contribution provided by the artist and poet Phillip Aijian demonstrates not only the skill of an experienced craftsperson gifted with detail and vision, but beautifully reveals how art and theology can meaningfully contribute to each other. It is our sincere wish that you enjoy this thought-provoking unity of words and images as much as we did. Phillip has been an artist since he was young, pursuing both poetry and music, though visual art was part of his family’s tradition, going back three generations on his mother’s side. While he started his graduate work in Shakespeare, it wasn’t until halfway through his PhD that he felt a visceral urgency to make art more frequently. Thus began the work on his first liturgical clock. If you want to see more of his theological and artistic expressions, please visit https://www.phillipaijian.com

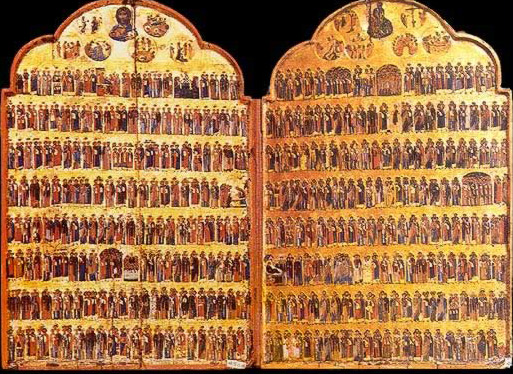

In 2006 I visited the “Icons of Sinai” exhibit at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. A Protestant among haloed Catholic saints, I was already out of my depth when I came to a menologium. The placard informed me that the menologium is used to observe the liturgical year through the commemoration of saints. Looking for a foothold, I tried and failed for an hour to find Christmas, thinking that I should at least be able to find Jesus prominently located somewhere among his flock.

Though its order eluded me, the menologium’s vision remained deeply embedded in my imagination. Most clocks allow us to orient future events to our present ambitions or needs. The menologium insisted that I reorient myself and my sense of time, cultivating a disposition and sight focused not on events or dates but on the Kingdom of Heaven: the fellowship of faith to which I belong and which awaits me in the New Jerusalem. In the years since the exhibit, I have endeavored to submit to this practice and vision through increased observation of the liturgical seasons. More recently, I have tried to incorporate this concept of time into my art.

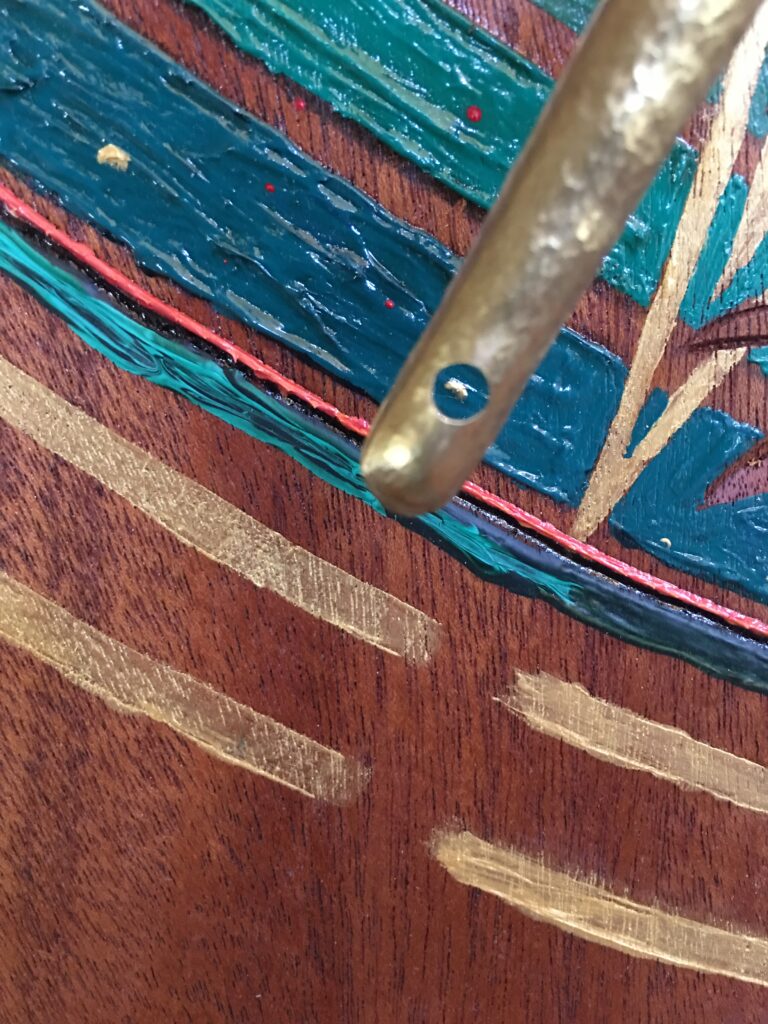

This is a liturgical clock. Measuring 40”x40,” it is made from wood, paint, shell, sand, silver, and bronze, and depicts salvation history combined with the Church year. Salvation history is represented through concentric circles emanating from the center of the clock. These circles represent significant events or seasons in the history of Israel and the life of Christ, beginning with the Garden of Eden at the center and extending to the New Jerusalem at the edges and corners. Just before the New Jerusalem, I have depicted the Church year with bands of color traditionally associated with different liturgical seasons. Time here is measured clockwise followed by the bronze hand, which makes one revolution each year.

At the center of these circles stands a cross which serves as the dial for the clock’s hand. The cross’s placement here, between the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge, signals the centrality of Christ in time and history. As Paul writes in Colossians 1:16-17, “…all things were created through him and for him. He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.”

The clock’s design seeks to reflect theology and Scripture through its material elements, beginning with the two trees in Eden. While the Tree of Life is painted and depicted with “positive” substance, the Tree of Knowledge is burned into the wood—its role in the Fall is represented as negative, damaged space. From this tree, tendrils of burnt wood extend through other elements of the clock. They form the ring of thorns surrounding the trees, representing the curses leveled against creation in Genesis 3 and moving on to the Tower of Babel—the flagship symbol in the ring of the City of Man. From here, these burnt channels extend through the clock’s depiction of salvation history until their progress is terminated by Christ’s crown of thorns. The sequence of images beginning with the Tree of Knowledge is burned into the wood in order to materially represent a spiritual reality— St. Augustine’s claim that evil has no substance itself but is a corruption of a good. Likewise, the path of sin represented in these thorns is not straight or predictable, but wasteful, bending, and curving in on itself.

Burning the wood also represents the view that human industry is tainted with the corruption of the Fall. The City of Man depicts not only Babel, but iconic structures from both the modern and ancient world, including the Eiffel Tower, St. Basil’s Cathedral in Red Square and the Statue of Liberty. Thus, one of the clock’s narratives is our journey from the City of Man to the City of God. By placing the modern alongside the ancient, the clock suggests that without God, human effort can only seek to build Babel. The work of sin is only halted by the work of Christ at Calvary. The clock depicts this emancipation by overlaying Christ’s crown of thorns over the top of a circular groove carved into the wood, each side of which is painted purple, demonstrating the tearing of the Temple veil.

As the work of sin terminates at Calvary, Christ’s atonement becomes the basis for redemption and new life. The clock depicts this with carved floral images that bloom out from the crown of thorns. Taken from Biblical references, hagiography, and artistic tradition, these plants celebrate the life of Christ and the life of the Church. Those celebrating Christ are rendered with carved, sculpted wood that rests on top of the clock. Like the Tree of Life, their positive substance represents the perfected, completed work of Christ while the mix of positive and “relief carving” on the other side of the clock (during Ordinary Time) indicates that the work of the Church has begun, but awaits its perfection and completion.

The clock strives to represent Christ’s fulfillment of Old Testament tropes and prophecies in other ways as well. The circle representing Israel’s slavery, exodus, and forty years in the desert is rendered in paint, but also includes grains of sand which invite contemplation through tactile engagement. This symbol of Israel’s wandering is revisited in the clock’s representation of Christ’s temptation in the desert. Where Israel fails, Christ succeeds, and the clock depicts this by representing the waters of his baptism with braided silver wire and the conclusion of his temptation with inlaid brass wire. Between these shining bands of metal the desert temptation is depicted with sand, but this sand is mixed with abalone.

Abalone proves one of the most significant materials in the clock’s witness to the dual nature of Christ. Though the interior of an abalone shell presents dazzling iridescent colors, these emerge only after the abalone dies and its flesh is stripped away. A living abalone possesses an unremarkable appearance. So it was with Christ: the Incarnation disguises a divinity that few recognize. Thus, abalone is used where Christ’s divinity is most evident—in his Transfiguration and in his Resurrection. But the clock also incorporates the less dazzling outer shell of abalone to gesture toward Christ’s humanity. Spanning a range of reds, these fragments are embedded in the top of the cross dial, again in the paint of Good Friday, and finally in the breast of the Lamb of God in the New Jerusalem.

This correlation between the cross and the Lamb of God is one of the clock’s multiple symbolic patterns, which unite the liturgical year to salvation history. In some of the circles marking Israel’s history, I have depicted symbols connected to Christ and the Church. Using silver wire, the clock visually aligns these symbols with different seasons: Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, Easter, and Ordinary Time. Each of these patterns is oriented to the cross. The celebration of Holy Week, for example, belongs to a sequence that begins with Abraham’s ram in the thicket, includes Moses’ bronze serpent, and finally, portrays the eucharistic symbol. The clock invites its viewer to ask, “What does Good Friday have to do with the Lord’s Supper? With Jonah? With the patriarchs and the tabernacle?” The questions posed through these linked images aim to enrich the meditation and celebration of each season in its passage.

The clock requires some interaction and engagement from the individual or community who use it to “tell time” as the liturgical season progresses. The hand of the clock must be turned by hand, and the hand has a viewing port at its tip. These features of motion and focus are reminders that the life of faith requires something of us. The hand moves slowly, and its aperture is not wide. The view that it offers cannot satisfy the desire to see or comprehend all the elements or questions the clock elsewhere considers. This detail attempts to demonstrate that while some questions may elude our grasp, hope and purpose are found by viewing our lives and places in history through the work of Christ on the cross who, in all seasons and times, invites us to orient ourselves to himself.

Phillip Aijian is a writer, artist, and educator. He earned a PhD in Renaissance drama and theology from the University of California at Irvine as well as an MA in poetry from the University of Missouri. He lives in California with his wife and children. His chapbook, Homeless God, is available through Californios Press.